Solving systems of first-order ODEs like a baller

some ballin' tips and tricks

I recommend reading/skimming this post first on ways to very quickly identify the characteristic polynomial, eigenvalues, and eigenvectors.

We are going to be discussing how to solve systems of differential equations with constant coefficients like a bodacious baller.

\begin{equation} \label{prob} \textbf{x}’=A\textbf{x},\quad \textbf{x}(0)=\textbf{x}_0 \end{equation}

Specifically, there are ways to make solving the \(2\times2\) case absurdly quick. Especially with complex or defective eigenvalues. There will also be some ways to make \(3\times3\)’s less awful, and some tricks for some special cases of larger matrices.

We will assume the matrices we discuss are all real (and not the zero matrix).

2x2s

\[\begin{equation} \bf{x}'=\begin{pmatrix}a&b\\c&d\end{pmatrix}x \end{equation}\]The first step for any of these problems is to find the eigenvalues. Without them, there’s almost nothing we can do. As mentioned before, I have a post on ways to greatly speed up this process. Regardless, to find the eigenvalues we start by calculating the trace and the determinant.

Reminder that the trace is the sum of the diagonal entries \(\operatorname{tr}(A)=a+d\) and the determinant of a \(2\times2\) matrix is \(\det(A)=ad-bc\). We will also use the fact that the trace is the sum of the eigenvalues, and the determinant is the product.

General Observations

Before we go and find the eigenvalues specifically, here are some things we can say about the behavior of the solutions just by inspection of a \(2\times2\) matrix’s trace and determinant:

- If \(\det(A)<0\), then the origin will be a saddle point (and the eigenvalues are real and distinct)

- If \(\operatorname{tr}(A)>0\), then the system is unstable

- If \(\det(A)=0\), then the sign of \(\operatorname{tr}(A)\) will determine if the system is stable (positive or zero = unstable, negative = stable). There will be infinitely many critical (equilibrium) points. Additionally, the eigenvalues will be \(\lambda=0,\operatorname{tr}(A)\).

- If \(\operatorname{tr}(A)=0\), then the eigenvalues differ by a sign, and the sign of \(\det(A)\) will determine if the system is stable: positive = stable center, negative = saddle, zero = improperly unstable (I made up that name. I don’t know if there’s a proper term for it). Also, regardless of the determinant, it will always be possible to easily solve the problem with one of the formulas which will be presented shortly.

- If \(\det(A)>0\), then the sign of the trace is the sign of the real parts of the eigenvalues (thus, if the trace is positive then the origin is a source, and if the trace is negative then the origin is a sink).

- If the matrix is symmetric, the eigenvalues are real and not defective. If the matrix is skew-symmetric (\(A^T=-A\)), then origin is a stable center (and the eigenvalues are purely imaginary).

These are some pretty important things we can say before we even examine the characteristic polynomial. Not all of these are necessary conditions, however. For example, the trace can be negative and the system can still be unstable. These facts are all based on how the signs/values of \(b\) and \(c\) affect the roots of the quadratic \(x^2-bx+c\), as the trace and determinant will be those coefficients in the characteristic polynomial.

Finding Eigenvalues

If you can think of two numbers that add up to the trace and multiply to the determinant, then those will be the eigenvalues. If you cannot, then use the fact that the characteristic polynomial is

\begin{equation} \lambda^2-\operatorname{tr}(A)\lambda+\det(A)=0 \end{equation}

You don’t have to waste your time doing \(\det(A-\lambda I)\) every time.

How to solve them quickly

Now there are many different potential subcases of the three main cases of eigenvalues: real, complex, and defective. For certain common cases, there are some ballin’ tricks you can use to solve them really quickly: Matrix exponentials! Often, \(e^{At}\) can be very easy to calculate once you know the eigenvalues. If you need to solve an initial value problem, then matrix exponentials will be by far the fastest way to solve them. This is because the solution to the initial value problem \eqref{prob} will be

\begin{equation} \textbf{x}’=A\textbf{x},\quad \textbf{x}(0)=\textbf{x}_0\implies \textbf{x}=e^{At}\textbf{x}_0 \end{equation}

The Fast Formulas

Check if your matrix satisfies any of the following cases before you get down and dirty with eigenvectors:

I will copy the most useful formulas from my post about \(2\times2\) matrix exponential formulas:

- If \(A\) has a real determinant, \(\operatorname{tr}(A)=0\), and \(\det(A)<0\), then an eigenvalue of \(A\) is \(\lambda=\sqrt{-\det(A)}\), and

\begin{equation} \label{form1b} e^{At}=\cosh(\lambda t)I+\frac{\sinh(\lambda t)}{\lambda}A \end{equation}

- If \(A\) is real and has complex conjugate eigenvalues \(a \pm bi\), then

\begin{equation} \label{form2} e^{At}=\frac{e^{at}}{b}\bigg(b\cos(bt)I+\sin(bt)(A-aI)\bigg) \end{equation}

- If \(A\) has one defective eigenvalue \(\lambda\), then

\begin{equation} \label{form3} e^{At}=e^{\lambda t}\bigg(I+t(A-\lambda I)\bigg) \end{equation}

- Note: this will not be the fastest way for a singular \(2\times 2\). But if \(A\) is any sized singular matrix with a nonzero trace,

\begin{equation}\label{form1c} e^{At}=\frac{e^{\operatorname{tr}(A)t}A-(A-\operatorname{tr}(A)I)}{\operatorname{tr}(A)} \end{equation}

- Note: this will usually not be the fastest way for a \(2\times 2\) with distinct eigenvalues. However, if \(A\) does have distinct eigenvalues, then

In summary, using \(e^{At}\) for these cases not only removes the need to find eigenvectors, but also finds you the fundamental matrix. And the fundamental matrix turns solving initial value problems into calculating a simple matrix product.

The columns of these matrices will give you a fundamental set of solutions. So if you are able to just see what the entries will be, it’s possible to write down the answers without any scratch work. This applies most to the complex and defective cases. Also, in my opinion, it’s a true baller move to casually use a matrix exponential rather than find eigenvectors. ![]()

Distinct Eigenvalues Formulas

If \(A\) has distinct eigenvalues, then a matrix exponential will not be the fastest way to calculate the general solution. It is faster to just find the eigenvectors using the “Eigenvector Columns Theorem” discussed in the other post.

That said, while the ECT is the fastest way for any general solution, if you want the general solution for a general initial value problem, like \((x_0,y_0)\), then \eqref{distinct} is actually worth the time, as it is not too difficult to calculate.

- If \(A\) is singular and has a nonzero trace, then

- Choose any nonzero scalar multiple of a column of \(A\) and call it \(\textbf{v}_{\operatorname{tr}(A)}\)

- Choose any nonzero scalar multiple of a column of \(A-\operatorname{tr}(A)I\) and call it \(\textbf{v}_0\)

The general solution of \(\textbf{x}'=A\textbf{x}\) will be

\begin{equation}\label{form40} \textbf{x}=c_1\textbf{v}_0+c_2e^{\operatorname{tr}(A)t}\textbf{v} _{\operatorname{tr}(A)} \end{equation}

- More generally, if \(A\) has real and distinct eigenvalues \(\lambda_1,\lambda_2\), then

- Choose any nonzero scalar multiple of a column of \(A-\lambda_1I\) and call it \(\textbf{v}_{\lambda_2}\)

- Choose any nonzero scalar multiple of a column of \(A-\lambda_2I\) and call it \(\textbf{v}_{\lambda_1}\)

Yes, the numbers are flipped, it is not a mistake. The general solution of \(\textbf{x}'=A\textbf{x}\) will be

\[\begin{equation}\label{form4a} \textbf{x}=c_1e^{\lambda_1t}\textbf{v} _{\lambda_1}+c_2e^{\lambda_2t}\textbf{v}_ {\lambda_2} \end{equation}\]Examples of using all of these formulas can be found in a section below.

3x3s

With \(3\times3\)s, I recommend using some of the tricks in my eigen-tricks post. The first trick is also using the trace being the sum of the eigenvalues, and the determinant being the product, as this works for any sized square matrix.

If the matrix has nice entries and you can find a combination of 3 nice eigenvalues which satisfy the trace and determinant, it is almost surely the case that that combination will be correct. You can always calculate \(A-\lambda I\) for any of them, and if the result is singular then you know you are correct.

For example, if the trace and determinant are both \(6\), then \(1,2,3\) are numbers which add up to and multiply to \(6\), so they are a great guess for the eigenvalues. There was a \(3\times3\) matrix on my Differential Equations midterm which had a trace and determinant of \(6\) so I was able to find the eigenvalues by inspection!

If \(A-\lambda I\) is not singular, or you just can’t guess what they could be, then I’d move on to the characteristic polynomial

\begin{equation} \lambda^3-\operatorname{tr}(A)\lambda^2+(C_{11}+C_{22}+C_{33})\lambda-\det(A)=0 \end{equation}

where we are denoting the Cofactor of the \(ij\) entry of \(A\) as \(C_{ij}\).

A trick that works for any sized square matrix: If \(A\) is a scalar matrix off from being rank one, \(A=kI+vw^T\), where \(v\cdot w\neq0\), then we can use \eqref{form40}

\begin{equation} e^{At}=e^{kt}\left(\frac{e^{(v\cdot w)t}vw^T-(vw^T-(v\cdot w)I)}{(v\cdot w)}\right) \end{equation}

This is based on the extremely useful fact that

\begin{equation} e^{At}=e^{k t}e^{(A-kI)t} \end{equation}

Therefore, if the matrix exponential of \(A-kI\) is very easy to compute, you can calculate that matrix exponential and just multiply the result by \(e^{kt}\). An example of this with a \(3\times3\) is included at the very end.

Examples

2x2 examples

As you read these examples, keep in mind that as you become more experienced with using these formulas, the number of steps and amount of scratch work required becomes much shorter than what is written here. When I said you can do these absurdly quick, I genuinely mean that you can just write down the matrix exponential without scratch work a lot of the time.

Zero Trace

\[\textbf{x}'=\begin{pmatrix}7&-13\\1&-7\end{pmatrix}\textbf{x},\quad \textbf{x}(0)=\begin{pmatrix}x_0\\y_0\end{pmatrix}\]That initial condition would be relatively hard to solve with a system of equations… Luckily, if we can find \(e^{At}\), then solving the initial value problem will be no problem at all.

The trace of this matrix is \(0\) ![]() so we will be able to use one of the formulas guaranteed. The determinant is \(-7^2+13=-36\) which is less than zero, so we can use \eqref{form1b} and \(\lambda=\sqrt{-(-36)}=6\).

so we will be able to use one of the formulas guaranteed. The determinant is \(-7^2+13=-36\) which is less than zero, so we can use \eqref{form1b} and \(\lambda=\sqrt{-(-36)}=6\).

The solution to the initial value problem will then be

\[e^{At}\textbf{x}_0=\left(\cosh(6t)I+\frac{\sinh(6t)}{6}\begin{pmatrix}7&-13\\1&-7\end{pmatrix}\right)\begin{pmatrix}x_0\\y_0\end{pmatrix}\] \[\textbf{x}=\cosh(6t)\begin{pmatrix}x_0\\y_0\end{pmatrix}+\frac{\sinh(6t)}{6}\begin{pmatrix}7x_0-13y_0\\x_0-7y_0\end{pmatrix}\] \[\textbf{x}=\frac{1}{6}\begin{pmatrix}6x_0\cosh(6t)+(7x_0-13y_0)\sinh(6t)\\6y_0\cosh(6t)+(x_0-7y_0)\sinh(6t)\end{pmatrix}\]And that’s it!

Complex

\[\textbf{x}'=\begin{pmatrix}4&-6\\15&-2\end{pmatrix}\textbf{x},\quad \textbf{x}(0)=\begin{pmatrix}x_0\\y_0\end{pmatrix}\]Alright so trace and determinants are \(2\) and \(82\) respectively. Now that’s a pretty big determinant and a pretty small trace. If a quadratic has a large constant term and a small linear term then the roots are going to be complex. So let’s look at the characteristic polynomial:

\[\lambda^2-2\lambda+82=0\]Let’s complete the square since the middle term is even

\[(\lambda-1)^2+9^2=0\]Thus our roots are going to be \(1\pm9i\) (if that isn’t clear then just solve for \(\lambda\)).

Since our eigenvalues are complex, we can use \eqref{form2}

\[e^{At}\textbf{x}_0=\frac{e^{t}}{9}\bigg(9\cos(9t)I+\sin(9t)(A-1I)\bigg)\begin{pmatrix}x_0\\y_0\end{pmatrix}\] \[\textbf{x}=\frac{e^{t}}{9}\left(9\cos(9t)\begin{pmatrix}x_0\\y_0\end{pmatrix}+\sin(9t)\begin{pmatrix}3&-6\\15&-3\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}x_0\\y_0\end{pmatrix}\right)\] \[\textbf{x}=\frac{e^{t}}{9}\left(9\cos(9t)\begin{pmatrix}x_0\\y_0\end{pmatrix}+3\sin(9t)\begin{pmatrix}x_0-2y_0\\5x_0-y_0\end{pmatrix}\right)\] \[\textbf{x}=\frac{e^{t}}{3}\begin{pmatrix}3x_0\cos(9t)+(x_0-2y_0)\sin(9t)\\ 3y_0\cos(9t)+(5x_0-y_0)\sin(9t)\end{pmatrix}\]Which is very easy to plug into desmos!

Brief remark: If you want to use this to check if the solution you got through the normal method (let’s call it \(\textbf{x}_1(t)\)) is correct, then check if

\[e^{At}\textbf{x}_1(0)=\textbf{x}_1(t)\]Now, I don’t know about you, but I think this is much easier than finding the eigenvector by solving for the null space of

\[\begin{pmatrix} 3-9i&-6\\15&-3-9i\end{pmatrix}\]Just looking at that matrix makes me want to switch majors. You could use the Eigenvectors Column Theorem or \((b,\lambda-a)\), which would make it slightly less awful. But you would still have to multiply by \(e^{(1+9i)t}\), take the real and imaginary parts as our two solutions, and then solve a difficult system of equations for that initial value problem.

You have to do exactly none of that with this matrix exponential method. Work smart, not hard.

Defective

\[\textbf{x}'=\begin{pmatrix}4&-9\\1&-2\end{pmatrix}\textbf{x},\quad \textbf{x}(0)=\begin{pmatrix}x_0\\y_0\end{pmatrix}\]Trace and determinant are \(2\) and \(1\). \(1\) and \(1\) add up to \(2\) and multiply to \(1\), so it looks like we have a repeated eigenvalue of \(1\). Thus, we can use \eqref{form3}

\[e^{At}=e^{t}\bigg(I+t(A-I)\bigg)\] \[e^{At}\textbf{x}_0=e^{t}\left(I+t\begin{pmatrix}4-1&-9\\1&-2-1\end{pmatrix}\right)\begin{pmatrix}x_0\\y_0\end{pmatrix}\] \[\textbf{x}=e^{t}\left(\begin{pmatrix}x_0\\y_0\end{pmatrix}+t\begin{pmatrix}3x_0-9y_0\\x_0-3y_0\end{pmatrix}\right)\] \[\textbf{x}=e^{t}\begin{pmatrix}x_0+(3x_0-9y_0)t\\y_0+(x_0-3y_0)t\end{pmatrix}\]That’s literally it. No eigenvector. No solving \((A-\lambda I)\eta=\xi\). This is it. We’re done. Q.E.D.

Now for the cases for which a matrix exponential is not ideal.

Singular

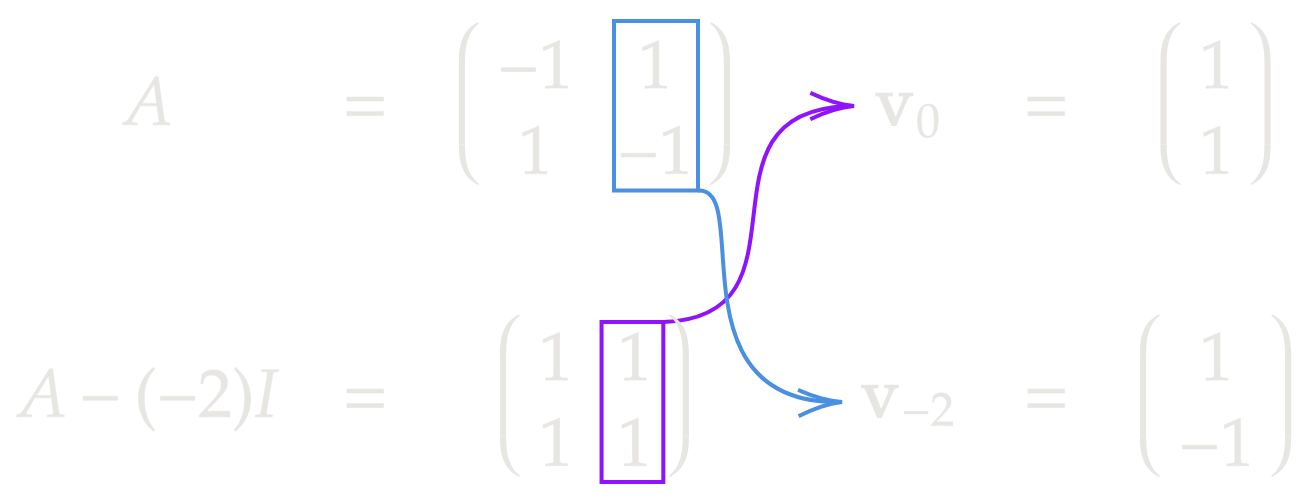

\[\textbf{x}'=\begin{pmatrix}-1&1\\1&-1\end{pmatrix}\textbf{x}\]Well, this is clearly a singular matrix, since the rows are scalar multiples of each other. If you don’t see that right away, that’s okay. You would calculate that \(\det(A)=0\). The trace is \(-2\), which is nonzero, so we know the eigenvalues will be \(0,-2\). We may then use \eqref{form40}:

Our solution is then

\[\textbf{x}=c_1\begin{pmatrix}1\\1\end{pmatrix} +c_2e^{-2t}\begin{pmatrix}1\\-1\end{pmatrix}\]Done.

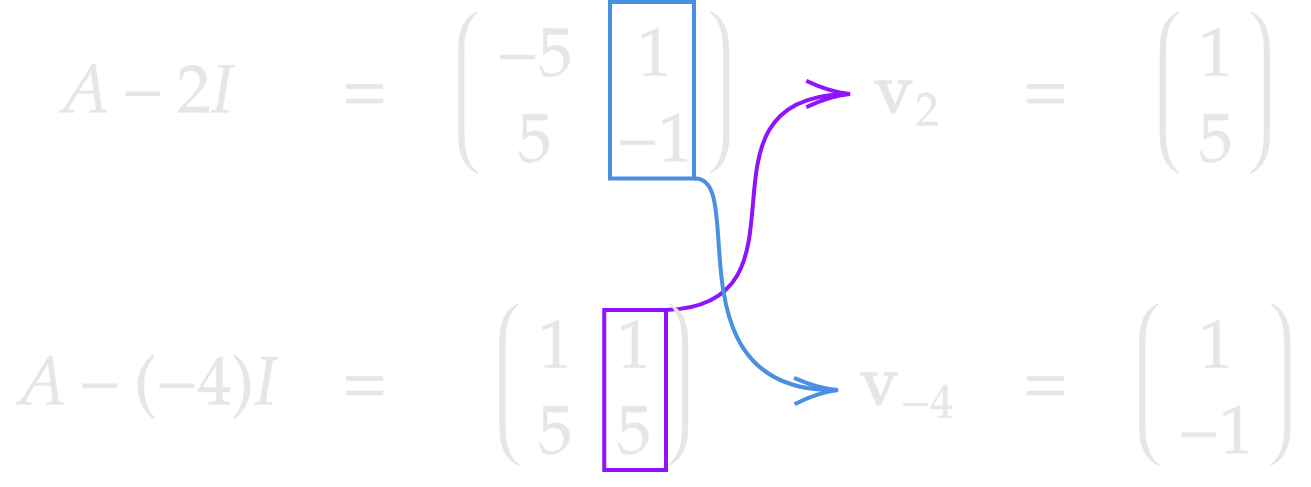

Real and Distinct

\[\textbf{x}'=\begin{pmatrix}-3&1\\5&1\end{pmatrix}\textbf{x}\]We know the drill by now: Trace and determinant are \(-2\) and \(-8\). \(-4\) and \(2\) add up to \(-2\) and multiply to \(-8\), so they are our eigenvalues. Now we obtain the eigenvectors like so:

Thus the solution is

\[\textbf{x}=c_1e^{2t}\begin{pmatrix}1\\5\end{pmatrix} +c_2e^{-4t}\begin{pmatrix}1\\-1\end{pmatrix}\]Absolute black magic, I know.

Quick note: If \(A-\lambda I\) end up being something like \(\begin{pmatrix}3&-9\\-6&18\end{pmatrix}\), you don’t have to choose \(\begin{pmatrix}3\\-6\end{pmatrix}\) or \(\begin{pmatrix}-9\\18\end{pmatrix}\). I would just go with \(\begin{pmatrix}1\\-2\end{pmatrix}\). Nothing necessarily wrong with any of the previous two, though. But I wouldn’t use them ![]()

Off by a scalar matrix example

Take \(A=\begin{pmatrix}-2&1&1\\1&-2&1\\1&1&-2\end{pmatrix} =-3I+\begin{pmatrix}1&1&1\\1&1&1\\1&1&1\end{pmatrix}\)

\[A=-3I+\begin{pmatrix}1\\1\\1\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}1&1&1\end{pmatrix}\]Since \(\begin{pmatrix}1\\1\\1\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}1&1&1\end{pmatrix}\) is a rank one matrix, its matrix exponential is easy to calculate with \eqref{form1c}. Since its trace is \(3\), if we call \(v=(1,1,1)\) we have

\[\exp\left(vv^Tt\right)= \frac{1}{3}\left(e^{3t}vv^T-(vv^T-3I)\right)\] \[\exp\left(\begin{pmatrix}1\\1\\1\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}1&1&1\end{pmatrix}t\right)= \frac{1}{3}\left(e^{3t}\begin{pmatrix}1&1&1\\1&1&1\\1&1&1\end{pmatrix}-\begin{pmatrix}-2&1&1\\1&-2&1\\1&1&-2\end{pmatrix}\right)\] \[\exp\left(\begin{pmatrix}1&1&1\\1&1&1\\1&1&1\end{pmatrix}t\right)= \frac{1}{3}\begin{pmatrix}e^{3t}+2&e^{3t}-1&e^{3t}-1\\e^{3t}-1&e^{3t}+2&e^{3t}-1\\e^{3t}-1&e^{3t}-1&e^{3t}+2\end{pmatrix}\]So to get \(e^{At}\), we just need to multiply by \(e^{-3t}\) (since \(A=-3I+vv^T\))

\[\exp\left(At\right)= \frac{e^{-3t}}{3}\begin{pmatrix}e^{3t}+2&e^{3t}-1&e^{3t}-1\\e^{3t}-1&e^{3t}+2&e^{3t}-1\\e^{3t}-1&e^{3t}-1&e^{3t}+2\end{pmatrix}\]