Linear Constant Coefficient ODEs

the most important topic in an ODE class

Ah, “second order constant coefficient linear homogeneous ordinary differential equations”. What a wonderfully concise name for one of the most common types of problems in differential equations.

This is, in my opinion, the most important topic in an intro to ODEs class. Probably the best thing about these kind of equations is that they are easily solvable, and can be thoroughly understood. The same cannot be said for most ODEs, even linear ones!

We will start with second order homogeneous equations, and then briefly discuss how these topics generalize to higher order equations. Finally, I will leave some resources to discuss nonhomogeneous equations (or make another post on that later).

Intro

First, we need to talk about exponentials, because they are crucial. Specifically, what I am going to call a “simple (complex) exponential”. A simple exponential is an exponential function like

\[y=Ce^{\lambda t}\]Where \(\lambda\) is some complex number. That’s right! We are going to definitely need complex numbers for this topic. But let that be for later. For now, you can imagine \(\lambda\) being some real number like \(2\).

For now, just observe that \(y'=\lambda Ce^{\lambda t}=\lambda y\). We can rearrange that to say that

\[y'-\lambda y=0\]One way to articulate this (in linear algebra terms), is to say that simple exponentials are linearly dependent on their derivatives. That just means that we can scale them by numbers and add them up in a way that gives zero. For example,

\[\left(\frac{d^2}{dt^2}e^{2t}\right)-5\left(\frac{d}{dt}e^{2t}\right)+6e^{2t}=0\]Because when we evaluate those derivatives we end up with

\[2^2e^{2t}-5(2e^{2t})+6e^{2t}=0\]So, this means that \(e^{2t}\) is a solution to

\[y''-5y'+6y=0\]How could we have found that? Well, I’ll tell you.

The characteristic polynomial

Take the example equation we had before

\[y''-5y'+6y=0\]How might we solve this? Well, we already observed that exponentials are linearly dependent on their derivatives, so we might expect that our solution is a simple exponential. Then, we will use the idea behind most techniques in differential equations: “the solution probably looks like this, so let’s plug it in and solve for the unknowns”.

That is, plug in \(y=e^{\lambda t}\) and see what happens! When we do so, we get

\[\lambda^2e^{\lambda t}-5\lambda e^{\lambda t}+6e^{\lambda t}=0\]We can factor out the exponential to get

\[(\lambda^2-5\lambda+6)e^{\lambda t}=0\]Now, one of the cool things about exponentials is how they are never zero. So, clearly, we need \(\lambda^2-5\lambda+6=0\). And this is just a quadratic equation! We call it the “characteristic polynomial”.

In general, we get the characteristic polynomial from the differential equation like so

\[ay''+by'+cy=0 \implies a\lambda^2+b\lambda+c=0\]Pretty easy, huh? Just take the coefficients directly and factor the quadratic. Eventually (assuming you can factor polynomials or complete the square in your head…), you can solve these problems without writing down anything.

Back to our example,

\[\lambda^2-5\lambda+6=(\lambda-2)(\lambda-3)=0\]Then it appears that we need \(\lambda=2\) or \(\lambda=3\). Meaning that it seems that two solutions are \(y_1=e^{2t}\) (like we saw before!) and \(y_2=e^{3t}\).

We can check to see if the same thing that happened with \(e^{2t}\) happens with \(e^{3t}\).

\[\left(\frac{d^2}{dt^2}e^{3t}\right)-5\left(\frac{d}{dt}e^{3t}\right)+6e^{3t}=3^2e^{3t}-5(3e^{3t})+6e^{3t}=0\]And it does! So we have two solutions, now. But are there more? Yes!

Take, for example, \(y_3=e^{2t}+e^{3t}\). Plugging this in gives

\[\begin{multline} (2^2e^{2t}+3^2e^{3t})-5(2e^{2t}+3e^{3t})+6(e^{2t}+e^{3t})\\ =(2^2e^{2t}-5(2e^{2t})+6e^{2t}) +(3^2e^{3t}-5(3e^{3t})+6e^{3t})=0 \end{multline}\]Notice exactly what happened here. We added up the solutions to get \(y_3\), but when we plugged it all in, we were able to just separate them, and they both went to zero like they did individually. We call this the Principle of Superposition!

Now, you may choose to read my incoherent explanations of linear independence and superposition. You could read my explanation on why we need two solutions for second order equations. Or, you could just skip all of it and get into how we solve these equations.

Superposition

“Principle of Superposition” might sound scary and intimidating, but it’s just a result of two important properties of the derivative

\[(cf(t))'=cf'(t),\quad (f(t)+g(t))'=f'(t)+g'(t)\]Basically, you can pull a constant outside of a derivative, and you can split up the derivative of a sum as the sum of derivatives. We can combine these facts to say

\[\begin{equation} (c_1f(t)+c_2g(t))'=c_1f'(t)+c_2g'(t) \end{equation}\]Note: When we start adding and scaling stuff we call it a “linear combination”. So \(c_1f(t)+c_2g(t)\) is a “linear combination of \(f(t)\) and \(g(t)\)”.

We can apply this to linear differential equations. For example, if we define the “differential operator” for the generic second order linear differential equation

\[L[y]=y''+p(t)y'+q(t)y\]Then watch what happens when we evaluate \(L[c_1y_1+c_2y_2]\):

\[L[c_1y_1+c_2y_2]=(c_1y_1+c_2y_2)''+p(t)(c_1y_1+c_2y_2)'+q(t)(c_1y_1+c_2y_2)\] \[L[c_1y_1+c_2y_2]=c_1y_1''+c_2y_2''+p(t)(c_1y_1'+c_2y_2')+q(t)(c_1y_1+c_2y_2)\]Now, if we separate the \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) terms,

\[L[c_1y_1+c_2y_2]=c_1(y_1''+p(t)y_1'+q(t)y_1)+c_2(y_2''+p(t)y_2'+q(t)y_2)\] \[L[c_1y_1+c_2y_2]=c_1L[y_1]+c_2L[y_2]\]Nifty. We can use this to say that if \(L[y_1]=L[y_2]=0\) (that is to say, \(y_1\) and \(y_2\) are solutions to the differential equation), then

\[L[c_1y_1+c_2y_2]=c_1L[y_1]+c_2L[y_2]=c_10+c_20=0\]Meaning that any arbitrary linear combination of solutions is also a solution.

However, this may all look like mumbo jumbo to you. What you should get from this is the following:

“ya scale a solution, ya get a solution. ya add solutions together, ya get a solution. ya do both at once, ya get a solution.”

So, to get every solution, we take an arbitrary linear combination of our individual solutions. As long as you got all the individual solutions you were supposed to get (see next section), we call this the “general solution”.

For our example of \(y''-5y'+6y=0\), this would mean that the general solution is

\[y=c_1e^{2t}+c_2e^{3t}\]Linear independence

I will admit, for the sake of simplicity, I was a little vague about how we get our general solution. You may, for example, say that \(y_1=e^{2t}\) is a solution, and \(y_2=2e^{2t}\) is also a solution. So can we not say that our general solution is \(y=c_1e^{2t}+c_22e^{2t}\)?

No, we can’t. The reason should hopefully make sense: that doesn’t give us every solution! There is no constants \(c_1,c_2\) such that \(c_1e^{2t}+c_22e^{2t}=e^{3t}\). We need a \(y_1\) and \(y_2\) such that \(c_1y_1+c_2y_2\) can give us every possible solution.

So how do we check if our choice of solutions is gucci? Well, we have a test for that! It’s called the Wronskian (do not look Wronskian up on Urban Dictionary).

\[\begin{equation} W[y_1,y_2](t)=\det\left(\begin{bmatrix}y_1(t)&y_2(t)\\y_1'(t)&y_2'(t)\end{bmatrix}\right) =y_1(t)y_2'(t)-y_1'(t)y_2(t) \end{equation}\]If the Wronskian of two functions is nonzero at a point \(t_0\), then the functions are linearly independent at that point, and they form a fundamental set of solutions which can solve any initial value problem centered at \(t_0\).

One important result that you can verify with this is that \(y_1=e^{at}\) and \(y_2=e^{bt}\) are linearly independent if and only if \(a\neq b\). Meaning that we don’t have to worry and check if \(e^{2t}\) and \(e^{3t}\) are independent or not using the wronskian. They are independent because \(2\neq3\).

How does this tell us anything? Where does it come from? If you couldn’t care less, then skip here! If you are genuinely curious, though, we can see it like this:

Imagine you are trying to find the solution to the initial value problem with initial conditions \(y(t_0)=y_0, y'(t_0)=y'_0\). Given your two solutions \(y_1,y_2\), you would find the constants \(c_1,c_2\) such that \(y=c_1y_1+c_2y_2\) by solving the system

\[\begin{array}{ccccc} c_1y_1(t_0)&+&c_2y_2(t_0)&=&y_0\\ c_1y_1'(t_0)&+&c_2y_2'(t_0)&=&y'_0\\ \end{array}\]If you would like to see a derivation that does not use linear algebra, please see here. Otherwise, we’re just going to shift the burden of proof to linear algebra.

Thank you, linear algebra

The system of equations can be written as a matrix system

\[\begin{bmatrix}y_1(t_0)&y_2(t_0)\\y_1'(t_0)&y_2'(t_0)\end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}c_1\\c_2\end{bmatrix}= \begin{bmatrix}y_0\\y'_0\end{bmatrix}\]Let’s denote this matrix \(\mathbf{W}(t_0)=\begin{bmatrix}y_1(t_0)&y_2(t_0)\\y_1'(t_0)&y_2'(t_0)\end{bmatrix}\) and rewrite this system as

\[\mathbf{W}(t_0)\mathbf{c}=\mathbf{y}_0\]The invertible matrix theorem tells us this system of equations has exactly one solution if and only if \(\det(\mathbf{W}(t_0))\neq0\). Therefore, we are guaranteed to have a unique solution to the initial value problem if \(\det(\mathbf{W}(t_0))=y_1(t_0)y_2'(t_0)-y_1'(t_0)y_2(t_0)=W[y_1,y_2](t_0)\neq0\).

Emphasis on guaranteed. It’s possible to solve an initial value problem if you don’t have every solution. It’s just not always possible. For example, using the “not general solution” of \(y=c_1e^{2t}+c_22e^{2t}\), you can solve the initial value problem

\[y''-5y'+6y=0,\quad y(0)=2, y'(0)=4\]The solution is just \(y=2e^{2t}\). But you can no longer solve it if we change it to

\[y''-5y'+6y=0,\quad y(0)=2, y'(0)=5\]This is why \(y=c_1e^{2t}+c_22e^{2t}\) doesn’t work as a general solution. We need \(e^{3t}\) to solve this one.

As a final note, when a determinant is nonzero, it means that the columns are linearly independent. This is why we say that the Wronskian tells us if a set of given functions are linearly independent or not.

How many solutions to expect

I have not yet explained why only two solutions are sufficient for a second order equation. The short answer is that an \(n\)th order linear equation will have \(n\) linearly independent solutions. So, for second order, that means two. One way to think about it is “two derivatives means two arbitrary constants”. If that’s good enough for you, you can skip this section. But if you’re like me and you want to know why, then continue.

The answer can get pretty technical, so I will leave a relatively simple explanation that cites the all important Picard–Lindelöf existence and uniqueness theorem. We don’t have to worry at all about when solutions will exist or if the theorem will apply, because constant coefficients guarantees existence everywhere (since it trivially satisfies the requirements of the theorem).

- The existence and uniqueness theorem guarantees that a second order initial value problem with two conditions must have a unique solution.

- Since this must be true for any two arbitrary initial conditions, one function is not enough. However, two functions which are linearly independent will be able to satisfy any two arbitrary initial conditions (thanks linear algebra).

- If there was a third linearly independent solution \(y_3\) (i.e. it is not a linear combination of the first two), then that would contradict the uniqueness of the solution \(y=c_1y_1+c_2y_2\) which satisfies \(y(0)=y_3(0), y'(0)=y_3'(0)\).

Real Roots

Okay! So, either you read through all or some of my convoluted attempts at explaining superposition, linear independence, and the fundamental assumptions underlying how we solve these problems, or you didn’t. If you didn’t, here is a tl;dr:

second order means two different solutions. gotta have different power constants or it ain’t gucci.

Either way, let’s get onto the different cases we encounter when solving the characteristic polynomial!

Distinct roots

This is the case we were dealing with before. It’s the simplest and is the most straightforward. As mentioned back in Linear independence, if the power constants are different, then they are trivially linearly independent.

In summary, if the roots to the characteristic polynomial are \(a\) and \(b\), then the general solution is

\[y=c_1e^{at}+c_2e^{bt}\]Repeated roots

Consider the differential equation

\[y''+4y'+4y=0\]Characteristic polynomial is \(\lambda^2+4\lambda+4=(\lambda+2)^2\). To get it to be zero we need \(\lambda=-2\), and there is no other solution for \(\lambda\). So we get the solution \(y_1=e^{-2t}\). But now we have run into a problem.

Where is the second solution?

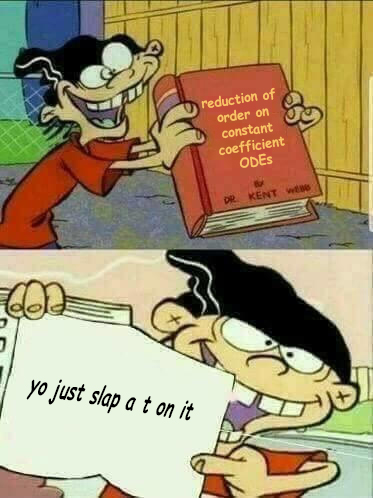

In general, for a second order equation, to get a second solution when you only have one, you can use reduction of order to get another. But we’re not going to worry about that at all! Instead, I will impart the wisdom that reduction order bestows upon you when you apply to it to constant coefficient equations:

yeah so the second solution is just \(y_2=te^{-2t}\).

In general, if you get a repeated root of \(a\), then the general solution is just

\[y=c_1e^{at}+c_2te^{at}\]Complex roots

Take, for example,

\[y''+4y'+13y=0\]Characteristic polynomial is \(\lambda^2+4\lambda+13=0\). We can complete the square to get

\[(\lambda+2)^2+9=0\]So, it appears we have no real solutions. If we solve for \(\lambda\) though, we get that \(\lambda=-2\pm3i\). Then, is the solution going to be this?

\[y=c_1e^{(-2+3i)t}+c_2e^{(-2-3i)t}\]Well, yes and no. See, the mathematics community is a bit discriminatory against complex solutions. They’re not seen as being real solutions. This is especially true when the original problem involves exclusively real terms. So we’re going to have to make our solutions real before our professor gives us any credit.

So what do we do? Well, as it turns out, we can just take the real and imaginary parts of either solution, and that will give us two linearly independent solutions!

Real and imaginary parts of solutions

Why is this true? Well, if the differential equation is all real, and you put in a complex solution, we can use linearity. Suppose that the solution is \(y(t)=u(t)+iv(t)\), where \(u(t)\) and \(v(t)\) are real functions. Then,

\[L[y]=L[u+iv]=L[u]+iL[v]\]Under the assumption that \(L[y]=0\), we get that

\[L[u]+iL[v]=0\]Since the differential equation is real, \(L[u]\) and \(L[v]\) are both real as well. And the only way that \(a+bi=0\) is if \(a=b=0\). So,

\[L[u]=0,\quad L[v]=0\]Meaning they are two solutions individually. Note that this also means that \(u-iv\) is a solution as well.

One thing that isn’t too difficult to prove with the Wronskian is that

\[\begin{equation} W[u+iv,u-iv](t)\neq0\iff W[u,v](t)\neq0 \end{equation}\]What about our example? What are the real and imaginary parts of \(e^{(-2+3i)t}\)? For that, we need Euler’s formula!

Eulers formula

If you are unfamiliar with what it means to raise \(e\) to a complex number, you can read this (and ignore the circular logic that comes from that post mentioning linear constant coefficient differential equations). But the basic summary which you can take as fact is that

\[\begin{equation} e^{ix}=\cos(x)+i\sin(x) \end{equation}\]Based on properties of exponentials, we can then say that

\[\begin{equation} e^{(a+bi)x}=e^{ax}\cos(bx)+ie^{ax}\sin(bx) \end{equation}\]The final solution

Onto the final solution (to second order linear constant coefficient homogeneous ordinary differential equations)! If we take the real and imaginary parts of \(e^{(-2+3i)t}=e^{-2t}\cos(3t)+ie^{-2t}\sin(3t)\), we get

\[y=c_1e^{-2t}\cos(3t)+c_2e^{-2t}\sin(3t)\]And, in general, if the roots of the characteristic polynomial are \(a\pm bi\), then the general solution is

\[y=c_1e^{at}\cos(bt)+c_2e^{at}\sin(bt)\]Summary

In summary, given the differential equation

\[ay''+by'+cy=0\]Where \(a,b,c\) are real (and \(a\neq0\)). If the roots of \(a\lambda^2+b\lambda+c=0\) are \(\lambda=\lambda_1,\lambda_2\) which are

- Real and distinct (\(\lambda_1\neq\lambda_2\)), then the solution is \(\begin{equation} y=c_1e^{\lambda_1t}+c_2e^{\lambda_2t} \end{equation}\)

- Real and identical (\(\lambda_1=\lambda_2\)), then the solution is \(\begin{equation} y=c_1e^{\lambda_1t}+c_2te^{\lambda_1t} \end{equation}\)

- Complex conjugates (\(\lambda=\alpha\pm i\beta\)), then the solution is \(\begin{equation} y=c_1e^{\alpha t}\cos(\beta t)+c_2e^{\alpha t}\sin(\beta t) \end{equation}\)

Higher order equations

What about third, fourth, or twentieth order equations? Actually, nothing changes. You just have more solutions. But the rules are exactly the same.

You still look at the characteristic polynomial, and the roots tell you the solutions.

More complex roots

If you get complex roots, you still just get a \(\cos\) and a \(\sin\). For example, in

\[y^{(4)}-2y'''+2y''-10y'+25y=0\]the roots are \(\lambda=-1\pm2i,2\pm i\). So our solutions will be

\[\begin{array}{cccc} \lambda=-1\pm2i&\implies& y_1=e^{-t}\cos(2t),&y_2=e^{-t}\sin(2t)&\\ \lambda=2\pm i&\implies& y_3=e^{2t}\cos(t),&y_4=e^{2t}\sin(t)&\\ \end{array}\]The general solution is then

\[y=c_1e^{-t}\cos(2t)+c_2e^{-t}\sin(2t)+c_3e^{2t}\cos(t)+c_4e^{2t}\sin(t)\]More repeated roots

If a root is repeated, just keep slapping \(t\) on there. For example, in

\[y'''+3y''+3y'+y=0\]The only root of the characteristic polynomial is \(\lambda=-1\) (repeated three times). Thus, the general solution is simply

\[y=c_1e^{-t}+c_2te^{-t}+c_3t^2e^{-t}\]It’s also possible to have repeated complex roots. In the equation

\[y^{(4)}+4y'''+14y''+20y'+25y=0\]The roots are \(\lambda=-1\pm2i\), both repeated. So we still get solutions \(y_1=e^{-t}\cos(2t)\) and \(y_2=e^{-t}\sin(2t)\), but we also slap a \(t\) on there.

\[y=c_1e^{-t}\cos(2t)+c_2e^{-t}\sin(2t)+c_3te^{-t}\cos(2t)+c_4te^{-t}\sin(2t)\]And, that’s it! Really, this topic is more about factoring polynomials and doing algebra more than it is differential equations (once you get past the derivation). After that, it’s just converting the roots into solutions from the formulas.